Intro

We love energy projects, but we don’t always love the schemes and gimmicks some companies devise to deliver them. High cost, inflated savings, and questionable performance are all common faults that you should be on the lookout for you as you plan a project.

Just by reading this article you could save 15% or more on your next energy project.

Reason 1 – If the Project Cost is Inflated

Energy and sustainability projects are largely financially driven. Return on Investment (ROI) is an important metric as every customer wants to get the most work done at the best quality for their investment.

Unfortunately, some energy services companies inflate the cost of projects through inefficient delivery methods and “optimistic” savings calculations that disguise high costs with what looks like a good ROI.

We’ll talk more about inflated savings in our next section.

Let’s talk about the delivery side for now.

Most energy service companies essentially function as design-build general contractors. They put together the project and then hire other firms to complete the work.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with this methodology, especially when projects are complex and have many interactive strategies. Think about building a house by hiring 1 GC vs. 20 different trades.

However, some energy service companies (ESCOs) add unwarranted cost to projects. These high costs come from a few inputs.

High Labor Rates

Many companies are not transparent on the labor rates charged for in-house design and project management. Outside the ESCO industry, it is common to review hourly rate sheets prior to issuing a contract to a professional services firm. These rates can then be compared to the market for reasonableness vs. the firm’s qualifications.

Unfortunately, many ESCOs do not show their internal labor rates. This allows rates to be inflated 20-80% above what is standard for similarly qualified positions procured outside an ESCO.

Transparency is the key to a customer determining if these rates are fair. Ask to see the rate sheet for all key positions staffing your project.

High Labor Hours

The costs charged by an energy services company are a combination of rates and hours. These hours should be verified for reasonableness vs. the project schedule and level of oversight provided.

If a project is primarily using turnkey subcontractors, the level of engineering and project management should be less than a project requiring more coordination with separate labor and material contracts. If a project is incurring higher subcontractor costs because the sub is providing turnkey design and delivery, the cost of the ESCO provided design and oversight should be offset accordingly to lower overall project cost.

By asking for a breakout of costs for design and project management as well as the rate sheet you can determine how many hours are included in the project. This should be reasonable for the level of difficulty in the project and associated schedule.

High Margins

What is a fair margin to cover a contractor’s overhead and profit?

In a competitive price proposal this question is answered by the market. Each respondent needs to be sharp on their margin in order to stay competitive on overall price.

Since many energy savings projects are procured based on qualifications instead of price, there is opportunity for higher margin after selection. We’ve heard of margins exceeding 30% on turnkey projects. This is much higher than most General Contractors completing similar projects that aren’t energy savings driven.

One reason given for these higher margins is the transfer of risk provided by the performance guarantee. To an extent this is valid, as long as the guarantee is valid. Similar to an insurance premium, there’s a quantifiable value to risk reduction.

However, as we’ll discuss in Reason 4 these guarantees often don’t actually transfer much risk to the energy services company. In these situations, it would be better to just estimate the savings and pay a lower margin on the project.

What’s the answer to the margin question?

Transparency.

If the project isn’t being competitively bid, the customer should be able to determine if they feel the overhead and profit is fair for the services being provided. All subcontractor bids should be available for review in an unaltered state. In-house costs (design, project management, etc.) should also be broken out to ensure they are reasonable. By reviewing these components you’ll be able to verify the actual margin in the project and ensure it is reasonable for the services being provided.

Lack of Competitive Bidding

Since most ESCOs are subcontracting the actual work, they should have a good procurement process of their own. This would include well written RFPs and at least 3 bids per Scope of Work (SOW).

To reduce effort, however, energy services sometimes just single source a subcontractor and have them complete the design and provide a no-bid price. This touches on our earlier point of inflated hours. This approach reduces the amount of time for the ESCO, but rarely results in the lowest subcontractor bid.

The answer?

You know by now….

Transparency.

The customer should have visibility to the subcontractor selection process and all bids as they are received without any markup applied by the ESCO.

Compounding Markup

We wrote an entire article on this topic so we won’t go in too much depth here.

Basically, if a subcontractor is putting 20% markup on labor and materials and the ESCO is putting 20% markup on that subcontractor, there’s a compounding effect of 44%. Cutting down a layer saves significantly. For this reason, a project should only be consolidated into a single contract if the scope of work is too complex and interactive to manage separately.

Reason 2 – If the Project Savings Are Inflated

Since the decision to proceed with a project is largely based on ROI, there’s an incentive for energy service companies to inflate savings projections. This helps them in two ways.

First, as we discussed in Reason 1, ESCOs can get away with high input costs and fat margins if the savings look good. A project that should cost $1M but is actually $1.2M looks like the same ROI if the savings are also $120k instead of $100k. The extra $200k in cost is essentially pure profit to the ESCO.

Secondly, even if the price is fair, more work can be done if savings are higher. If the customer is targeting a 5-year payback and the correct savings is $100k, then $500k of work can be done. If the savings are inflated to $120k, then $600k in work can be done and what still looks like a 5-year payback.

How are savings inflated?

Many ways, young Padawan.

Calculating savings requires a wide range of estimates and assumptions. There is always a margin of error in these estimates. However, good assumptions that are well defined and easily verified are key.

An Example of Inflated Savings

Take a lighting savings calculation for a tennis court that assumes the lights would run 600 hours a year. Rather than simply stipulating this assumption, we may be able to confirm by checking the electric meter serving the court. If available, it would be easy to see how many hours the existing lights are running by dividing annual kWh by KW of the lights.

Using this method, we may find the actual burn hours are closer to 200 hours a year, meaning the original calculation would have been overstated by 3x. Of course, the payback is much worse with this correct information.

Lighting is a simple example, but all calculations require good design and engineering. A well-documented report complete with reference to 3rd party standards, easily verified calculations, and all inputs and outputs should be provided for independent verification prior to the project being finalized.

Reason 3 – If it Isn’t Actually About Energy & Sustainability

Another tactic for energy services companies to grow projects is to include “avoided capital costs” as a “savings”. This is facilitated by some legislation that includes “avoided cost” without clearly defining this term.

Avoided capital essentially says that if a cost would be incurred in the future it can be included in the project and shown as a “capital cost avoidance”.

For example, if a chiller is 30-years old and needs to be replaced at a cost of $500k then the $500k is counted as a “savings” to the project.

This is saying “because you bought this chiller, you don’t need to buy this chiller, so it’s a savings”.

Weird, right?

Now, including the replacement chiller in the project isn’t necessarily a bad thing. If the chiller needs to be replaced and it will result in ongoing energy and maintenance savings, then it makes sense.

We must be very careful how we show costs/savings not in the actual historic baseline.

Our preference is to show the customer a cash flow pro-forma without cost avoidance. This shows the impact vs. their current annual budget. If there’s a gap because savings from the baseline does not cover the project cost, then the customer can decide if they have the budget available to proceed with the project.

Cost Avoidance can then be included (if legislation allows) once the customer fully understands that it is new money, not savings from their baseline.

Avoided Capital Cost Example

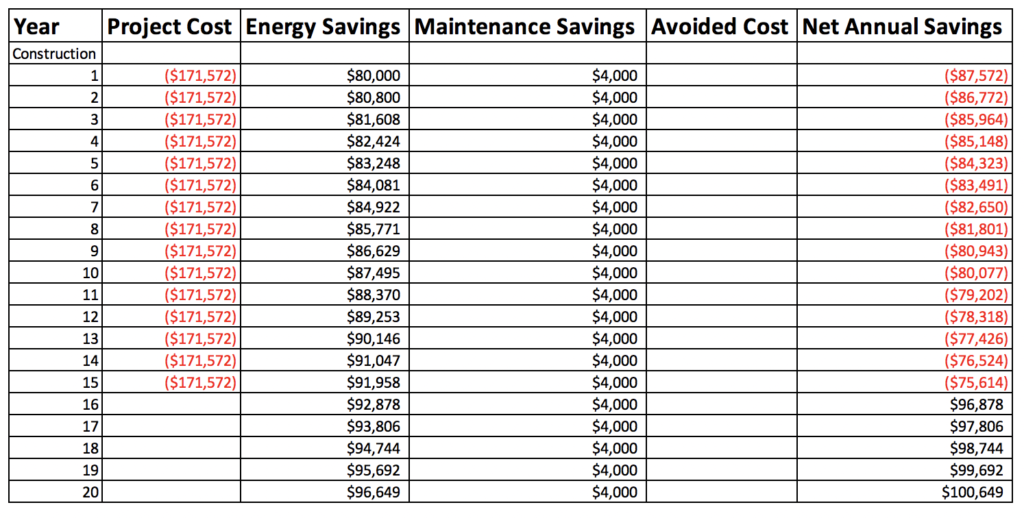

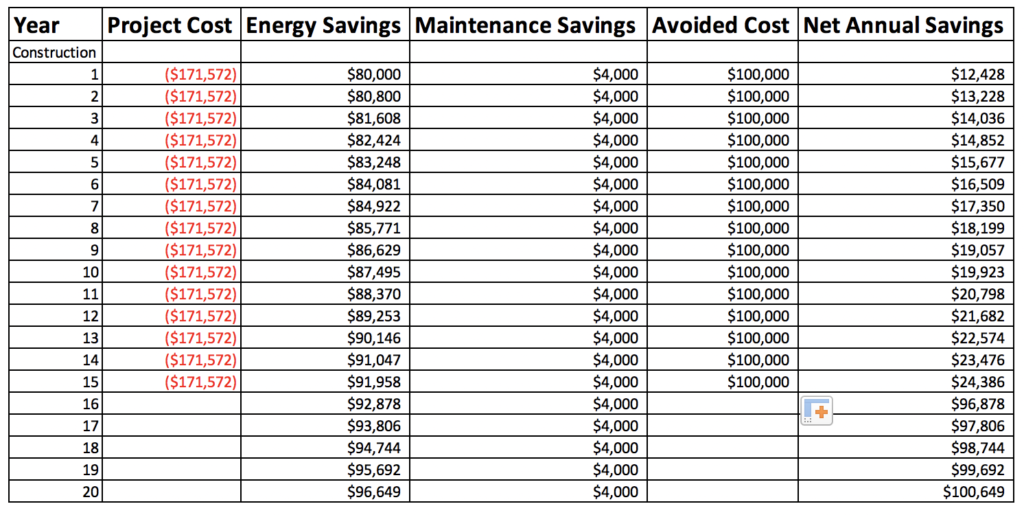

Below is an example of a $2M project financed over 15 years at 3.5%. The project saves $84k in the first year, yielding a simple payback of just under 24 years. This means the customer will need to come up with $87k in the first year to cover the difference between the project savings and the project payment.

Below, the “Avoided Cost” is shown as $100k/yr for 15 years. This is based on $1.5M of the project being capital costs that needed to be done anyway (HVAC, deferred maintenance, etc.). It makes the Net Annual Savings look positive and the simple payback appear much lower, but in reality this is new money that the customer will need to contribute in those years.

Reason 4 – If the “Guarantee” Isn’t Really a Guarantee

Whether you are completing a shared savings agreement, energy savings performance contract (ESPC), or Energy as a Service (EaaS), a major part of the contract is based on the savings realized from the project.

In the case of an Energy Savings Performance Contract, the guarantee is normally a contract with the ESCO, separate from the repayment terms with the financier.

In the case of shared savings agreements and Energy as a Service projects, the repayment amount is supposed to be based on the amount saved.

In either case, the measurement and verification of these savings is critical to the validity of any “savings” or “performance” guarantee. Most of the time it is being completed by the ESCO that completed the work.

The International Measurement & Verification Protocol (IPMVP) provides four main methods of quantifying savings. You can read more about these in this Energy.gov PDF if you’re interested.

The issue with the guarantees attached to some energy saving projects is they either:

1) don’t follow actual IPMVP protocols or

2) they misrepresent what is actually guaranteed.

LED Lighting Guarantee Example

Take for example LED lighting. The amount of energy dollars saved is a function of demand reduction (KW), consumption reduction (kWh), the cost of each of these components ($/KW and $/kWh). Since consumption (kWh) is the product of power (demand) over time, the burn hours of the lighting is a critical input as well.

Most projects will use IPMVP Option A, which basically measures the power draw (KW) before and after the retrofit.

This means the other inputs (burn hours, rates, etc.) still need to be properly defined and applied.

If they aren’t, the customer can end up not meeting the actual savings expectation even though the energy services company will claim to have met the contractual obligations and proper IPMVP protocol by measuring the power drop (KW).

“Avoided Energy Cost” Example

Another example of a poor savings guarantee is “avoided energy cost”. Some companies build in an escalation factor to their savings based on usage increases they claim would have happened if they hadn’t been there.

This is especially common in operational/behavioral type programs and shared savings agreements.

Essentially, they’re stating “if we hadn’t been here, your bill would be 3% higher each year” (or whatever percent is used).

This might sound reasonable at first and not a huge assumption, but those annual escalations end up compounding like interest and quickly become a major part of the so-called savings.

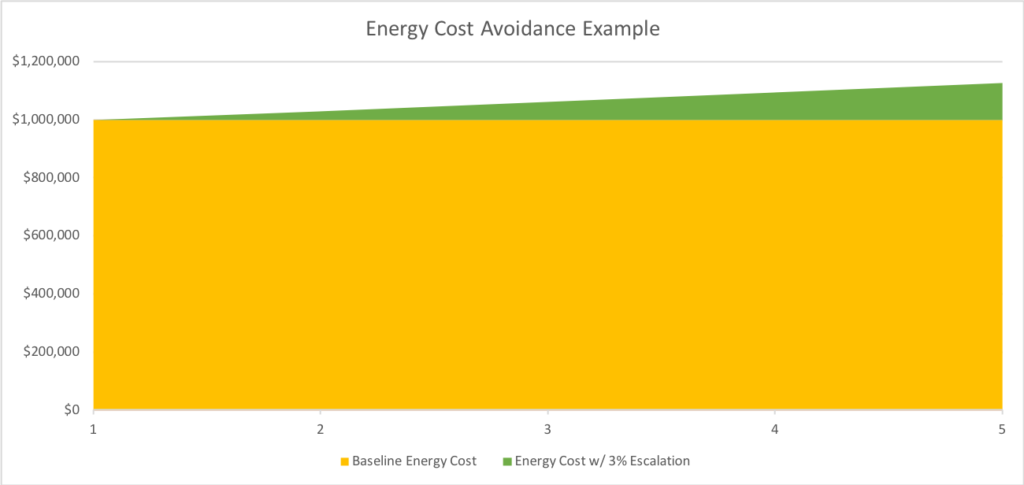

Here’s a graphic to help illustrate the concept based on a $1M utility spend and 3% escalation over 5 years.

By Year 5, the “Adjusted Baseline” is $1.125M. This means that even if the utility is still $1M, just like before the project/program, they would be showing $125k in Year 5 savings and $309k in total savings over the 5 Year contract.

Many of these contracts also have a shared savings component. This means that if the customer agreed to share savings 50/50 they’d be paying $155k to the ESCO even though the energy cost/consumption never changed.

We suspect many customers don’t even realize how much of their “savings” is actually just a clever assumption.

The Solution to Poor Performance Guarantees

One solution to avoiding the issue is separating the work being done from a guarantee. Projects can still have estimated energy savings as part of the business case, but the project is then delivered via design-build or some other method without any long-term guarantee. This should reduce the cost of the project as the energy services company does not need to measure and report savings each year and is not taking any long-term financial risk.

However, a properly structured guarantee does provide a benefit to customers that want to shift the financial risk of project performance to the third party.

In this case, we recommend engaging an independent owner’s representative to thoroughly review all savings calculations and assumptions. This is a regulatory requirement in some states (like Texas). However, the level of review and independence from energy services company varies, so the ideal situation is to find a firm independent from a recommendation by the energy services company. After all, the provider pushing for the sale has a vested interest to recommend firms that will not push back hard on their savings calculations.

Holisus offers these independent review services and would be happy to talk about your project.

Reason 5 – If the Agreement isn’t Clear

It has been said that you shouldn’t invest in anything you can’t easily explain to your grandmother.

The same could be said for energy projects.

We’ve seen a wide range of schemes allowing creative financing and procurement of projects. We’re not saying every one of these bad, but the agreement should be clear so that the owner can decide if meets their need.

If a project is “no cost” or uses “off balance sheet” financing, special care should be given. These are complex financial arrangements created by sophisticated attorneys and accountants. They may suit your needs, but it is wise to have an equally sophisticated team on your side to weigh all the pros and cons.

In addition to financing, savings guarantees and project procurement and delivery should all be easily understood and reviewed by an independent third party. Energy projects often mix all aspects of a project (financing, procurement, guarantees, etc.) into a single complex arrangement.

Buyer beware.

If it looks too good to be true, it likely is.

Conclusion

We are big proponents of energy projects and the value energy savings companies can provide. The benefits of these projects when properly designed, constructed, and verified are many. Owners can see strong financial returns, improved facilities, and enhanced sustainability.

However, we are very much against one-sided schemes and gimmicks. Transparency, integrity, and excellence should be part of every project.

Here at Holisus we offer consulting, owner’s rep services, and turnkey deliver of projects. We bring this spirit of integrity, transparency, and excellence to all we do.

If you’re looking at a project or program, send us a note.

Be Blessed,

Ira