Introduction

All entities with a substantial energy and water footprint should have a well-defined Energy & Sustainability (E&S) strategy. This reduces financial risk, enhances environmental stewardship, and increases operational efficiency and stakeholder (students, staff, etc.) well-being.

While having an E&S strategy is altruistic, if there is not a cost-effective plan to implement proposed tactics the plan will end up collecting dust on a shelf and have little of its intended impact. In this article we’ll discuss how contract structure, procurement choice, and financing options can be optimized to achieve best value in implementation cost.

Components of an E&S Strategy

As indicated in the tagline for our company, Holistic Utility Solutions, we believe that a good strategy considers all aspects of utility production and usage. Of course, sustainability can encompass more than just utilities, but since we specialize in electric, gas, and water we’ll address those here.

Our home page summarizes what a holistic strategy means to us, but in essence it considers the utility consumption, cost, operations, and production. Just as importantly, it considers how these interact.

For example, a strategy that uses chillers to produce cold water at night for daytime peak demand management may also see benefits of energy efficiency from the lower nighttime outdoor air temperatures and increased resiliency from the stored cooling capacity of chilled water. All of this should be considered and quantified for its interactive effects.

While this is all well and good, how do you go about building the business case to complete a single or multi-measure project to capture your identified tactics? Relatively small measures may not face a lot of financial scrutiny, but any project or program large enough to achieve meaningful impact will require substantial capital and become subject to more intense review.

In order to build a solid business with the right balance of cost and value, three main factors should be considered: Contract Structure, Procurement Choice, and Financing Option. We’ll explore each of these in detail here.

Contract Structure

Contract structure refers to what parties are involved in the actual design and construction of a project and how they relate to the owner. They can be structured and procured in a variety of methods (Design-Build, Design-Bid-Build, etc.), but ultimately the core structure and the resulting responsibilities and costs are what is important.

A Residential Home Example

To use a simple residential home example, if you need a toilet replaced in bathroom you have a few options to complete:

- Buy the toilet and do it yourself

- Buy the toilet and call a handyman to install

- Hire a plumbing contractor

- Hire a GC who hires a plumbing contractor

- Hire an architect to complete a design for you to bid to plumbers and/or GCs

- Hire a Design Build firm that designs the plumbing system and hires the plumbing contractor.

What is best for a toilet replacement (likely just calling a plumbing contractor) may not be best for an entire bathroom remodel (hiring a GC) or building a house (the architect or DB method).

The best solution ultimately depends on the skill and capacity of the owner, and the complexity of the scope of work. As more parties are introduced, cost may increase, but if each party is providing appropriate value this is not a negative by itself.

Common Contract Structures

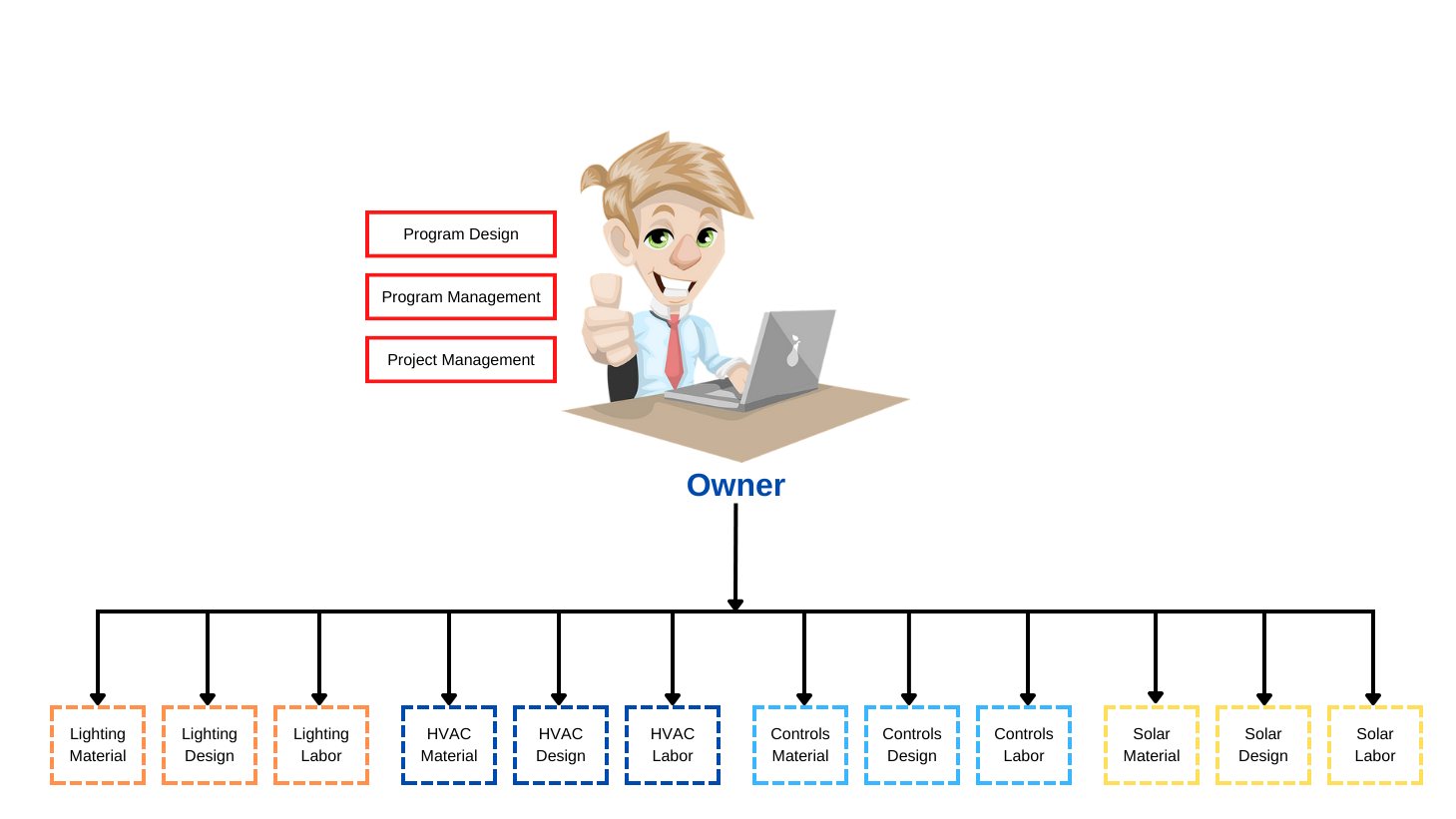

Let’s look at a common energy focused project that will include LED lighting, new HVAC system, HVAC controls, and a solar array. We’ll use this example to explore each type of common contracting structure with a graphical representation.

Scenario 1 – The Heavy DIY Owner

This is an owner who has significant in-house time and expertise available. For example, they may already have an energy manager, sustainability coordinator, engineer(s), project managers, etc.

They decide that they can keep cost the lowest by using an intensive DIY approach. What’s more, they want to absolutely minimize markup so they break apart every component in to its respective design, material, and installation components.

In our example of 4 main components in the scope of work (SOW), this works out to 12 different contracts!

While this would in theory keep the total cost of construction the lowest, the internal cost would be very high. The time to manage 12 different RFQ/RFPs is significant and the in-house resources would need to staff all aspects of program design, program management, and individual project management.

As the various trades interact, this coordination becomes increasingly difficult. For example, the mechanical and control systems are heavily interdependent. While having them on separate contracts is possible, the owner would have to be very knowledgeable and heavily involved to ensure the system is installed and operating well. There’s an increased risk of finger pointing with interactive trades if they are not bundled into a single contract.

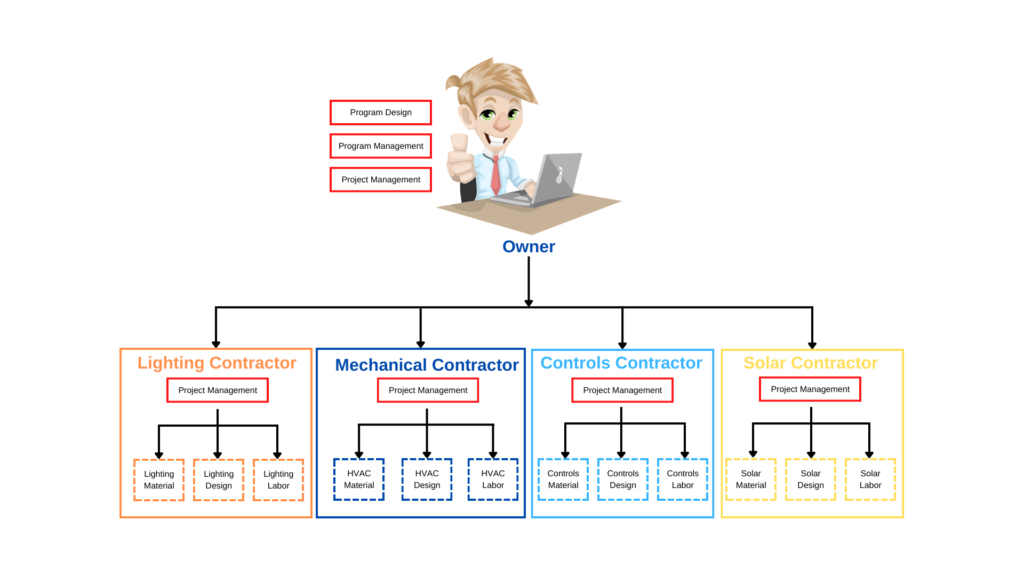

Scenario 2 – The Medium DIY Owner

This owner may look like the first scenario but they decide to strike a balance between external and internal cost. Rather than breaking apart every component they decide to source each contractor directly. This simplifies it to 4 contracts.

In this case the owner will still need to be heavily involved in the program design and management. Project level coordination between trades will also be important.

A lot of owners attempt this approach and it can work for a simple scope of work with only one or two trades, but there still needs to be a level of owner expertise and commitment to ensure it is procured and managed properly.

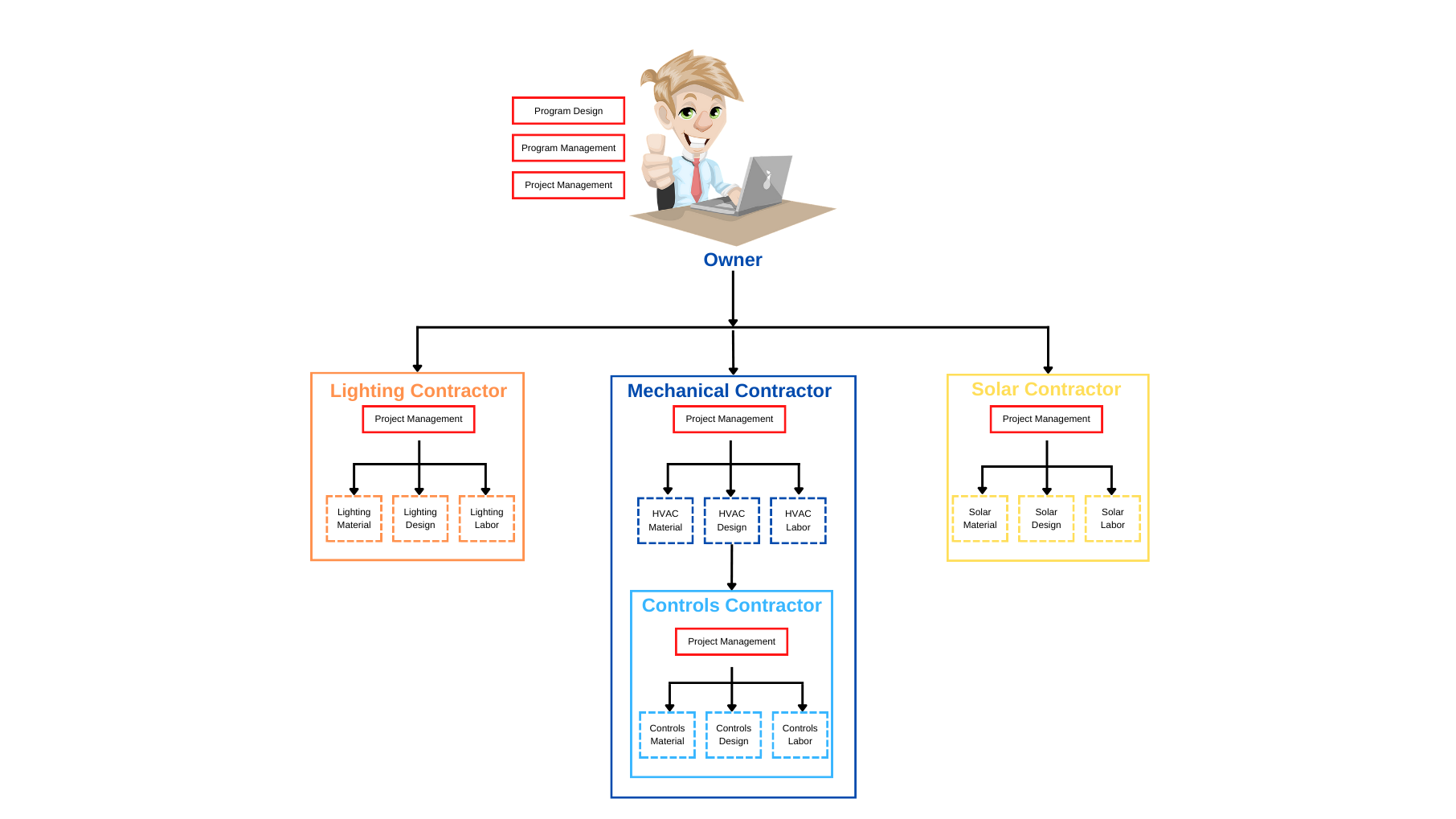

Scenario 3 – The Light DIY Owner

This owner recognizes that because of their level of interconnection, some trades are best served by combining contracts. A good example of this is the mechanical and controls. Since controls are to mechanical systems what the brain is to the body, it may make sense to have the controls contractor sub to the mechanical.

The DIY owner now has a multi-measure project that is fairly independent of one another. They should still have good internal expertise to consider the holistic strategy of a program design and management to maximize the overall system benefit. For example, the lighting system may include controls that could be merged with the HVAC system controls for lower overall cost and enhanced capabilities.

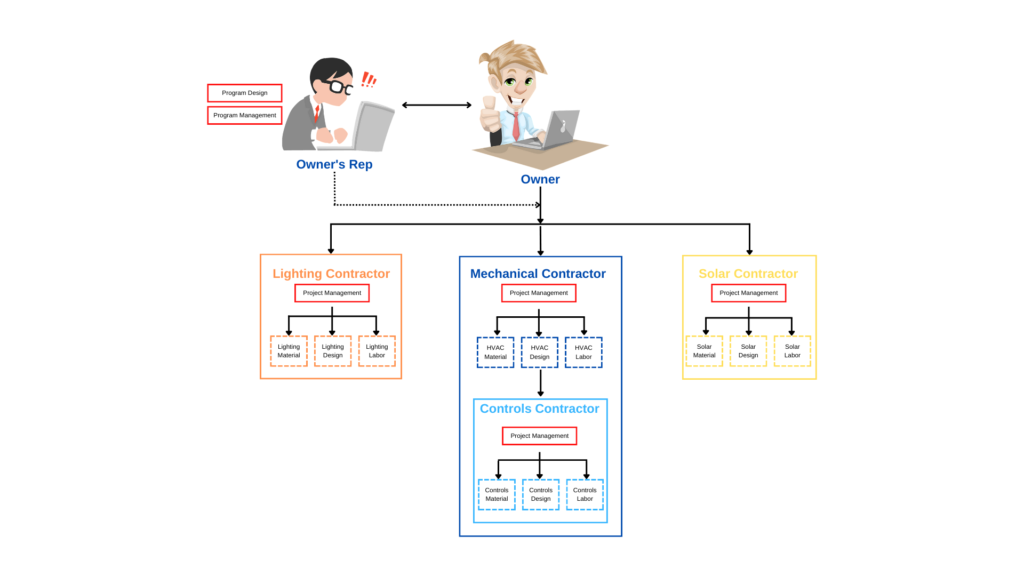

Scenario 4 – The Owner’s Rep Model

In this model, the owner recognizes that they could benefit from some external expertise and capacity to develop and manage a project. They engage an owner’s rep who helps develop the project goals and specifications, support the procurement process, and oversee implementation.

This is a great fit for complex projects with any size owner or even simple projects with owners that do not already have strong in-house expertise.

The owner’s rep model can be combined with any of the other contract methods we’re discussing here. The cost of the owner’s rep and their level of involvement depends primarily on the scope of the project and method of contracting, but in all cases they should provide value over and above their cost.

Note that the owner’s rep does not have direct oversight of the subcontractors, so they do not have to bond the subcontractors or guarantee their prices and delivery. They are a good compromise for an involved owner and will often more than pay for their fee in the value they provide.

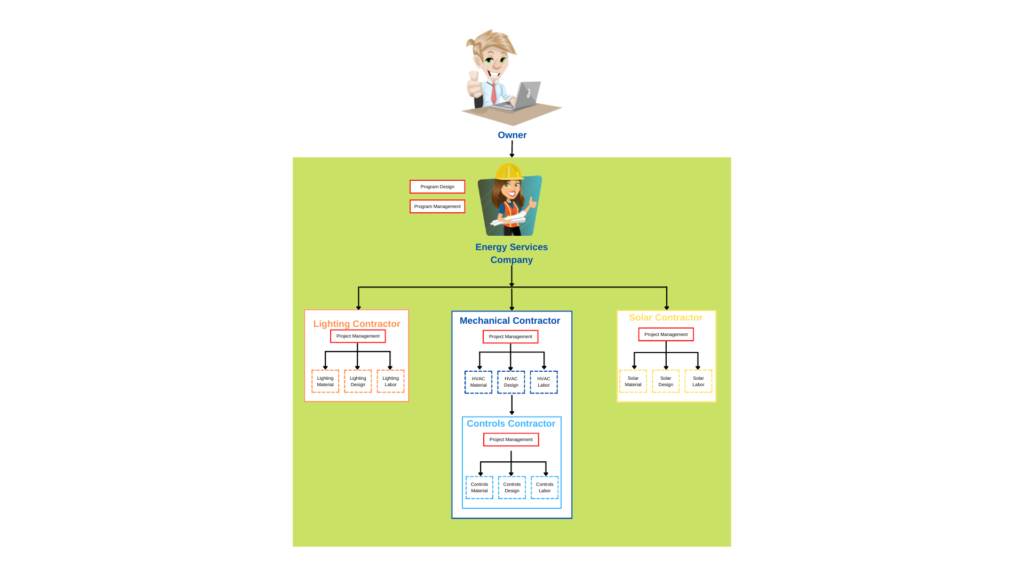

Scenario 5 – The Traditional Energy Services Company (ESCO) Model

This scenario is very common with ESCO companies, whether they are delivering via Design Build, Energy Savings Performance Contracts, Energy as a Service, or similar.

Almost all the burden and risk of project deliver is shifted from the owner to the ESCO. The ESCO in turn subcontracts the work. Oftentimes the detailed design of each SOW is often included in the subcontract. The ESCO provides a high level of program design and management, but they usually aren’t functioning as the actual engineer or project manager (site supervisor).

This can make sense for large complex projects across large geographies. In these cases, an owner may want to use a single company to develop and oversee the work, but that company does not have the local resources to go deeper into the delivery in each state.

This is perhaps the highest cost of all delivery models as there are multiple compounding levels of oversight and margin.

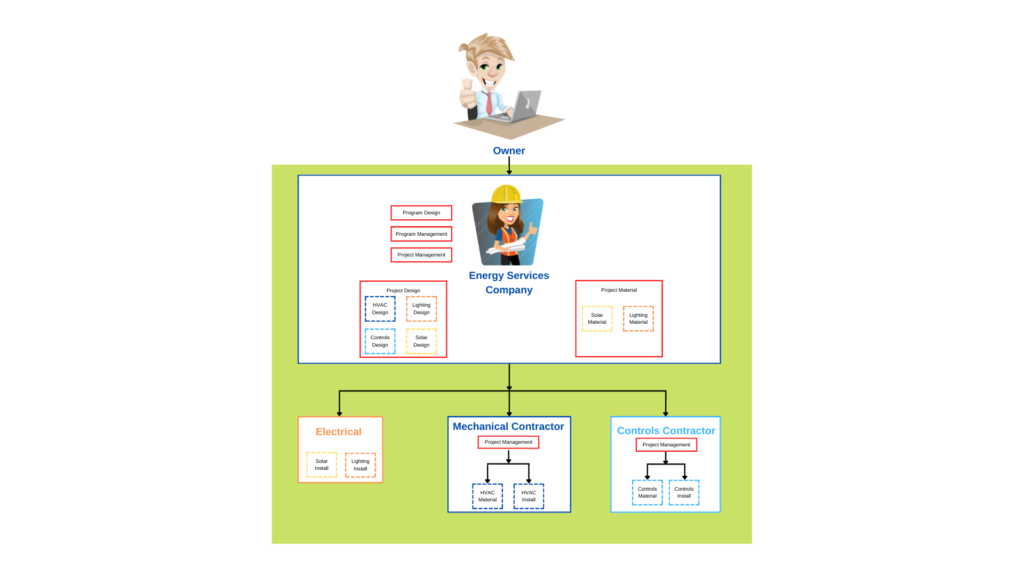

Scenario 6 – The Lean Energy Services Company (ESCO) Model

This model can take various forms and the graphic shown is just one iteration. The core idea though is that the ESCO looks to reduce compounding markup by self-performing more of the project design in-house and breaking apart the SOW into the various components for bidding. They may also pull out material and source directly from a manufacturer or distributor.

Rarely is an ESCO actually using their own employees to “turn the wrenches”. Rather, they subcontract the labor to strong local and/or specialized firms and provide the project oversight. The level of turnkey subcontracting vs. material/labor deconstruction in this model varies, but a good ESCO will have discussions with the owner about their goals and structure a project that strikes a good balance between cost, speed, and flexibility.

This model requires a lot more design and project management from the ESCO, so their costs in these areas are higher. However, since they are removing compounding levels of markup the overall cost should be lower than Scenario 5.

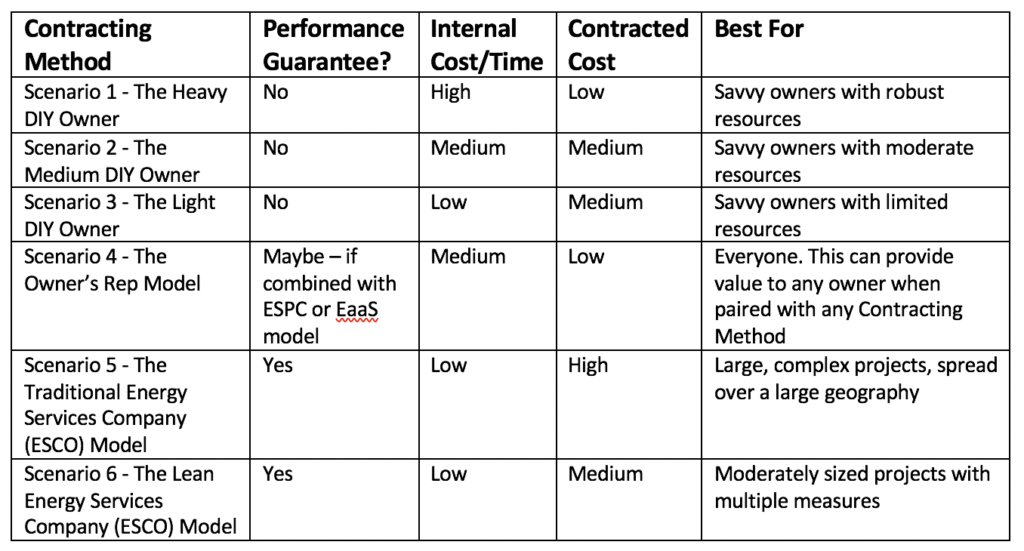

Contract Method Summary

No one of the scenarios shown above is inherently good or bad. Rather, they should be applied judiciously depending on the owner and SOW. A small customer with a simple project may do best to go direct to a single trade. A midsize owner with a multi-measure project may want the Lean ESCO approach while a large owner with a multi-measure project across multiple campuses needs the traditional ESCO model. All methods may benefit from an owner’s rep to help develop, procure, and oversee the project/program.

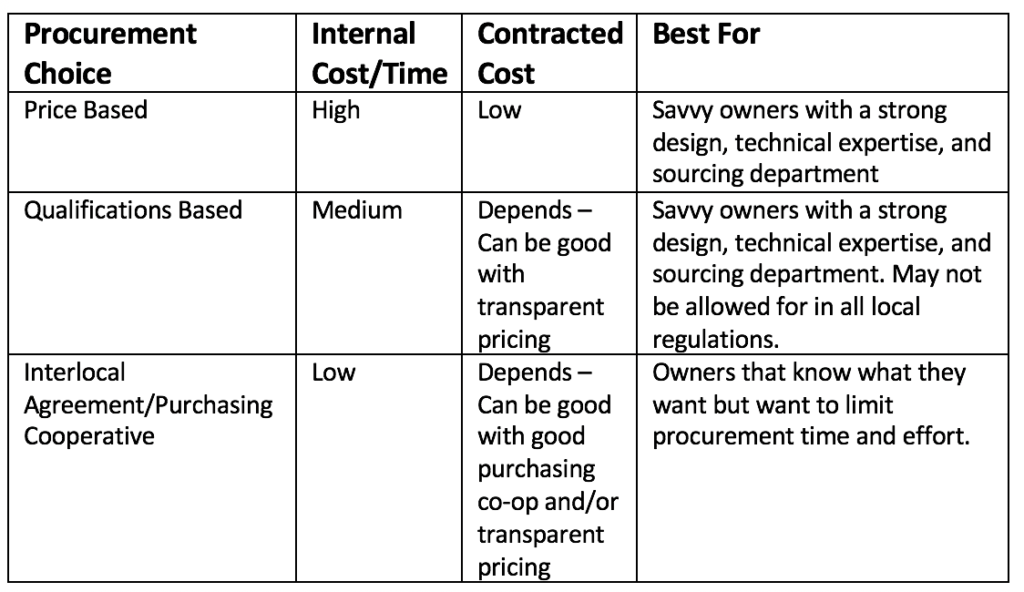

Procurement Choice

As we consider the best contract method, we also need to consider procurement options. Here’s a few common methods.

Price Based

These methods can either be fully based on priced or a mix of price and qualifications (RFP). In either case, a well-developed scope of work is needed so that the respondents can provide a bid with their response.

This method may require hiring an Engineer in advance to complete the design for bid. If being used with an Owner’s Rep delivery method, the rep should be engaged as early as possible as well.

The risk with priced based procurement is that “he who forgets the most, wins the job”. It isn’t to anyone’s benefit to have a contractor who is losing money on a project. Alternatively, a poorly written spec may allow substitutions that aren’t the owner’s actual intent. Lastly, a contractor with poor workmanship, safety standards, etc. may be low on price, but not deliver a safe and satisfactory project.

If price-based selection is used, qualifications should be considered as well. A good owner’s rep to oversee selection of the design team, specifications, and procurement process is money well spent.

Qualifications Based

A Request for Qualifications (RFQ) is often used for Energy Savings Performance Contracts (ESPC) and Design-Build projects. It is also standard for professional services, like engineers and architects.

In these procurement methods, the initial selection is based fully on the qualifications of the firm. Once the most qualified is identified, price is discussed. If an agreement can’t be reached, the next most qualified firm is negotiated with. This continues till an agreement is reached.

When done well, the RFQ method allows for selection of the best possible firm. The risk is “blank check syndrome”, where there’s little accountability for cost after selection.

The best way to manage this is through transparent pricing. If the selected firm openly shares their subcontract bids, internal cost, etc., the owner can negotiate accordingly to ensure a fair and profitable job for the ESCO without excessive cost to the owner.

Once again, an owner’s rep can more than pay for themselves in managing and negotiating an RFQ based selection.

Interlocal Agreement/Purchasing Cooperative

Purchasing Cooperatives, such as The Interlocal Purchasing System (TIPS) allow government agencies to select firms quickly and easily without the need to publish and evaluate formal pricing or qualification-based methods. These legally do so by pre-qualifying the contracts and offering them under the interlocal agreement provision.

These simplify and speed up the procurement process. However, and owner’s rep may still provide benefit in selecting the right firm, ensuring their approach is solid, and the pricing (if an RFQ based selection) is reasonable.

Procurement Summary

Procurement choices depend on regulations, company policy, and more. When flexibility is allowed, each should be considered based on the goals and resources of the organization.

Financing Options

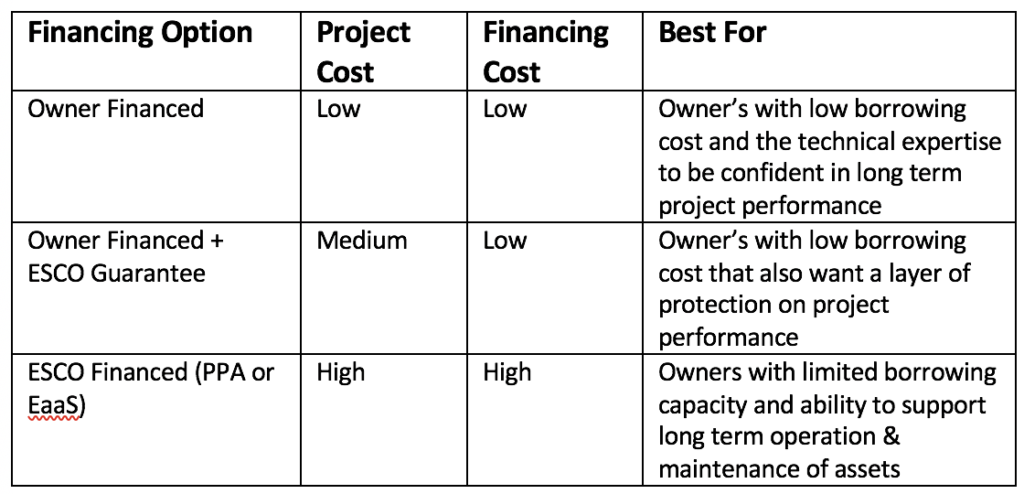

There is a myriad of financing options available and the purpose of this article is not to cover them all. Rather, we’ll discuss common methods used for energy & sustainability focused projects.

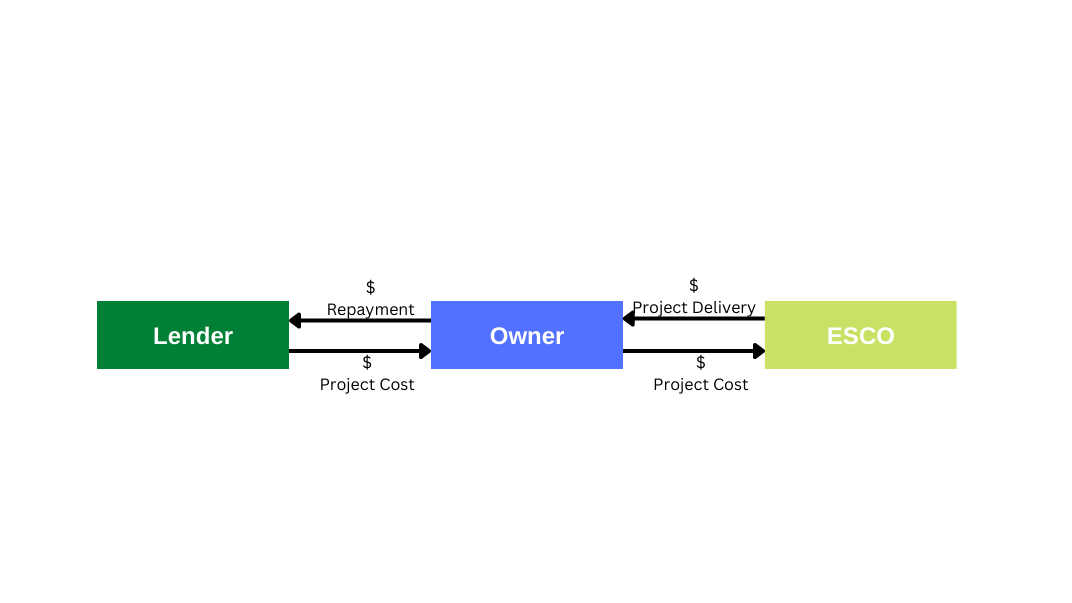

Owner Financed

Whether cash, debt, tax exempt lease, or other form of financing, this is where the owner holds title to the equipment and is responsible for any debt. Bonds, Certificates of Obligation, Maintenance Tax Notes, and special energy focused offerings are all examples of this.

If an owner is a public entity, they can often borrow at tax exempt rates. This gives them a cost of capital advantage over ESCO financing.

Owner financing can be paired with any of the contract and procurement options previously discussed. Generally, owner financing is the lowest overall cost.

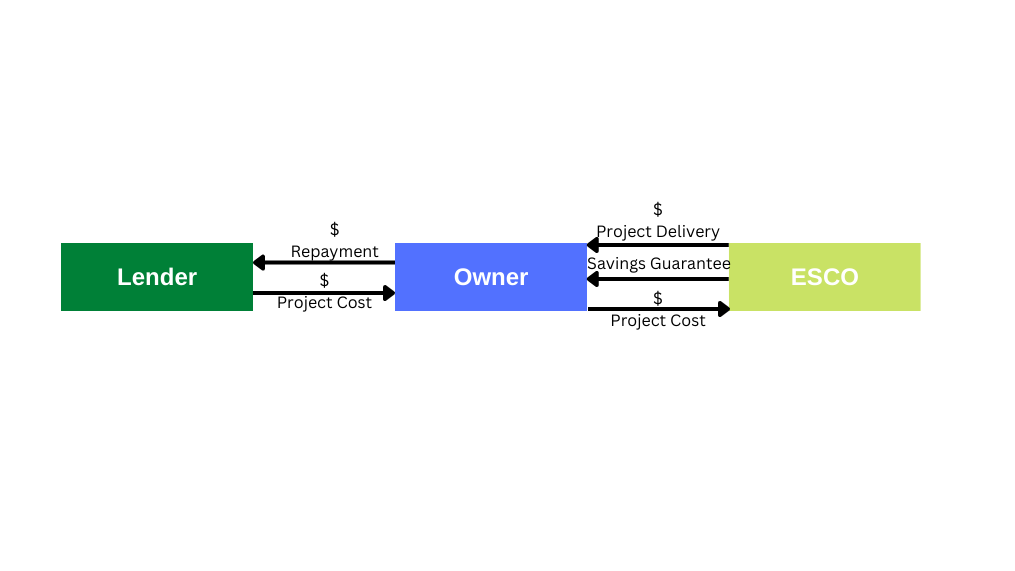

Owner Financed + ESCO Guarantee

If the owner is investing in the project primarily for the resulting savings, a guarantee of those savings may be desired to decrease owner risk. These guarantees are typically a separate agreement with the ESCO and based on some agreed upon Measurement & Verification (M&V) methodology.

These guarantees are common with Energy Savings Performance Contracts. It is important to note that the lender will still want repayment from the owner regardless of the ESCO guarantee. Should there be a shortfall in savings, the owner must then rely on their contract with the ESCO to recoup the guaranteed amount.

Guarantees are often complex and a knowledgeable owner’s rep can help ensure the owner is actually protected in the event of a shortfall. Some ESCOs simply stipulate savings or only take the minimum level of M&V steps required by law, leading the owner to believe there is a transfer of risk when in actuality the ESCO rarely if ever needs to make good on a shortfall.

Due to the risk transfer nature of a savings guarantee, there is usually a premium on cost. This is reflected in the project cost (ESPC will normally be more expensive than the same scope of work delivered via Design Build) and ongoing cost for recurring Measurement & Verification.

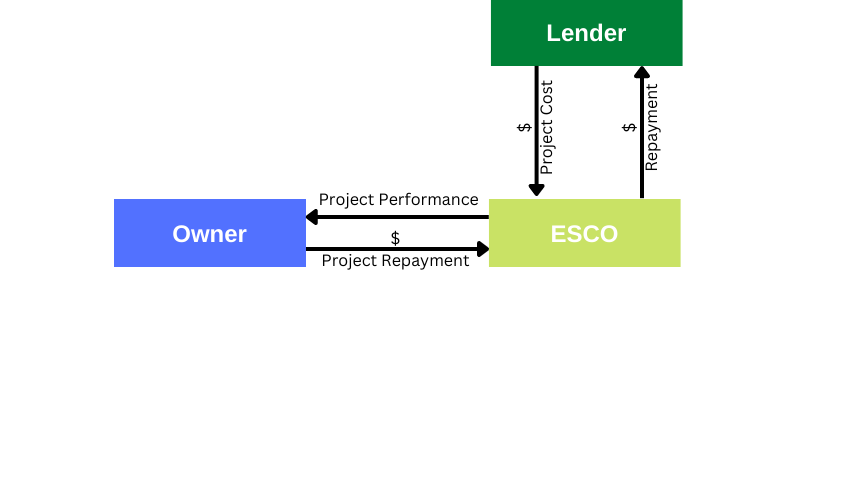

ESCO Financed (PPA or EaaS)

A Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) or Energy as a Service (EaaS) method combines the project finance with the performance of the project. PPAs are common with solar projects, where the project is actually owned by a 3rd party (the ESCO or a partner) and repaid based on the amount of power it produces.

When structured properly, this type of financing has the advantage of a built-in performance guarantee. If a project underperforms, the customer pays less. However, if it over-performs they may pay more. The details of these contracts can be complex. As with a savings guarantee in an ESPC project, the M&V methodology is key to ensure a transfer of risk. Terms on under or over-performance should also be carefully noted.

This method is also truly off-balance sheet. This means an owner with limited borrowing capacity can structure a project as a PPA/EaaS and retain their borrowing capacity for other non-energy related projects. This agreement may also come with Maintenance & Operations built in, simplifying owner’s operations.

The downside is that the cost of capital is typically higher, as the asset owner (ESCO) is a taxable entity. There may be other parties involved, such as tax equity partners, who also introduce fees and increase the cost. Given the risk transfer inherent in a well-structured contract, there is also a risk premium. All of this means a PPA/EaaS is often the most expensive way to finance a project.

However, when done well, this method can provide corresponding value in its risk transfer, ease of operation, and financial structure.

Financing Option Summary

Generally, owner financing is the lowest cost. The best way to evaluate this is to run multiple cash flow scenarios and use a discounted Net Present Value to compare the normalized cost of each.

Conclusion

Hopefully this has been helpful in helping you develop and deliver a cost-effective E&S strategy. No one method is best for all customers or projects, but when considered and evaluated carefully the right mix of price and value can be achieved.

We believe flexibility is key and support all varieties of the above methods. We’re always happy to chat if you’d like to discuss further or dig into a specific project with us.

Be Blessed,

Ira